Introduction

For many years now, CAMRA has been working hard to safeguard our legacy of pub interiors with real historic or architectural importance. We do this in four main ways:

-

raising public awareness thus enthusing people to visit these pubs;

-

encouraging owners of heritage pubs to appreciate and capitalise on their assets;

-

influencing decision makers at national level such as government departments and English Heritage;

-

use of the planning system, and listed building legislation in particular, to protect precious interiors.

The last of these obviously requires us to work closely with local planning authorities. In most cases we share common objectives around preventing harm to the local built environment. Several development control and conservation officers have told us that they would welcome written advice and guidance from us concerning historic pub interiors and this document attempts to do just that.

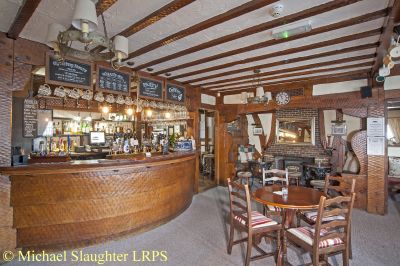

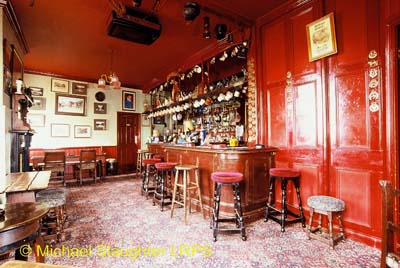

Bleeding Wolf, Scholar Green, Cheshire

Identifying pub interiors of major heritage importance

Of the 47,000 or so pubs in the UK, we estimate that less than two per cent have escaped drastic internal alteration in recent years. A major effort by CAMRA has therefore been to identify those which do retain historic plan forms and fittings to a greater or lesser degree. This is a continuing process with previously undiscovered gems still coming to light on the one hand and, sadly, identified pubs either closing or being unsympathetically refurbished on the other.

Our national inventory of historic pub interiors lists those interiors which we consider to be in the 'first division' which are designated three-stars. This category includes those interiors which are essentially intact since they were originally created (which could, for instance, include a 1930s design scheme within a Victorian building), and also pubs whose interiors, whilst not intact, contain features or rooms which are of truly national significance.

The second category are disigtaed two-stars and these identify interiors which are less intact or remarkable than those in the three-star category but which nonetheless possess considerable historic or architectural merit. A third category designated one-stars have either readily identifiable historic layouts or retain fittings, features or décor of special interest. Regional Real Heritage Pub Guides have been published for London, Scotland, East Anglia, the North East, Northern Ireland and Wales with Yorkshire, the East Midlands, the West Midlands, North West, the South West, and the South East.

The Inventories and Listing

Many pubs on the CAMRA Inventories are listed at Grade II with some at Grade II*. A lot, however, are unlisted. This in turn reflects the huge variety in historic pub interiors, ranging from spectacular late-Victorian extravaganzas to the simplest of rustic beer houses. Many of the interiors are, in architectural terms, straightforward and even prosaic; their preciousness lies in their survival from a different age. What was the 'norm' in 1910, 1930 or even 1960, is now extremely rare.

In 1999 CAMRA, in conjunction with English Heritage, appointed an expert caseworker, Dr Geoff Brandwood, to put forward applications for listings and upgrades, an exercise which has met with considerable success. Especially pleasing has been the agreement by English Heritage to recommend listing of several very simple interiors such as the Shakespeare, Dudley (a classic 'backstreet boozer') and the Eagle, Skerne, East Yorkshire (one of only fifteen pubs still without a bar counter).

A major objective of the Inventory initiative is to highlight the importance of many interiors which remain unlisted but which we still feel to be worthy of protection. The scope for the planning system to intervene here is obviously much more limited given that in most cases planning consent for alterations will not be needed. However, planning authorities may be able to bring influence to bear through informal channels.

Nor, of course, does statutory listing alone guarantee the survival of historic interiors and there have been several regrettable decisions by planning authorities to allow ruinous changes. We hope that this guidance will encourage authorities to examine applications concerning listed Inventory pubs with particular care and, as a rule, resist alterations which would spoil their character.

This is not to say that Inventory pubs must be preserved in aspic. With many of the smaller, simpler pubs in particular owners will claim, often justifiably, that they are no longer commercially viable. Solutions can however be found which avoid wholesale destruction. A good example is the Drewe Arms, Drewsteignton, Devon. Here the classic late Victorian historic core has been retained with new rooms added to the side which don't impact adversely on the original portion.

Historic Pub Interiors - What To Look For

Much of the pleasure to be derived from historic pub interiors stems from their enormous variety. Nevertheless, features of historic interest invariably fall within two categories - fixtures and fittings and planform/layout.

A word of warning though. Everything in the pub is not always what it seems because there are a lot of impressive fakes out there. What might look genuinely old could turn out to be a recent confection. Sam Smiths, the Yorkshire brewer, is especially adept at this kind of work, regularly installing multi-roomed layouts kitted out with period-style furnishings which really do resemble the genuine article. Although CAMRA strongly applauds this approach to pub design, it's important to realise that in most cases what you see now bears little or no resemblance to how the pub has looked in the past (there are exceptions - Smiths for instance have painstakingly restored the Princess Louise, Holborn, London to the architectural scheme which existed before its most recent alterations - which were in 1894!).

When carrying out inspections of Inventory candidates, CAMRA's Pub Heritage Group members take pains to seek out as much historical evidence as possible. We'd therefore like to think that if it's on an Inventory then you can be sure that the descriptions will highlight what is genuinely old (though we always stand to be corrected of course).

Where listed building consent is being sought for alterations to a pub then the application must of course be accompanied by fully detailed plans and elevations, now and intended, so that the planning authority can fully understand the extent and details of the proposals. What should planning officers be looking for in particular at this juncture? (and, indeed, when proposals affect unlisted buildings and there is scope to bring influence to bear).

Fixtures and Fittings

Here we are looking for items which are genuinely old - usually pre-Second World War though some material installed up until the 1960s may also be cherishable.

Arguably the most important areas are those around the bars as these are the 'theatre' of the pub, the main focal point and gathering place. There are two main elements - the bar back and the counter. The former (called a gantry in Scotland and Northern Ireland) can house glasses, spirits, other drinks, all manner of snacks from crisps to pickled eggs, the till and so on. Bar backs can range from basic shelves to elaborate combinations of wood and glass. Many are embellished by mirrors, some plain, some ornate.

The bar counter, sometimes described as the pub's high altar, comes in two parts - the long flat top and the supporting chassis. The former suffers much wear and tear so may have been replaced but the latter could well be old or original. Some are remarkably ornate.

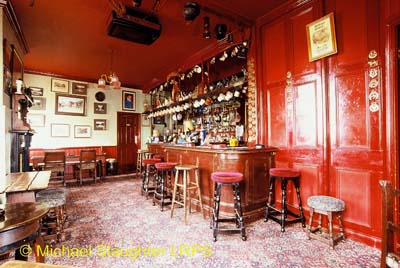

The Victorians and Edwardians in particular loved to embellish their pub interiors with ornate glasswork and mirrors. Windows would be etched and cut whilst internal work could see embossing, enamelling, gilding etc. However, designers from other eras have also left their mark such as Art Deco design from the 1930s. Any historic fittings which survive are precious and ought to be preserved. The same goes for ceramics, which being more difficult to remove or break have a better survival rate. Mosaic flooring and wall-tiling were both popular in the past and still lend beauty and distinction even in otherwise altered interiors.

Ornamental woodwork is also a feature in many historic interiors. It could constitute a wonderfully carved bar-back or elaborate fireplace; it could be something simple like panelling or fixed seating. Again, distinguishing what is actually old from what is more recent or installed repro can be quite tricky. Original seating might also be covered by newer fabrics and so not be immediately obvious.

Finally, there may be unusual features such as match strikers along the side of the bar counter, spittoons at its foot, spirit casks above the bar and ornate urinals which also add significantly to the architectural character.

Planform

The architecture of the pub has gone through many changes, the most notable tendency in recent times being the removal of separate rooms and screens/partitions to create single cavernous spaces. The latter are said (quite wrongly in our view) to offer advantages in terms of supervision and crowd control and licensing magistrates have often colluded in, and even driven, the rush for wall-removal. In reality it's these barn-like rooms with their emphasis on vertical drinking which are most likely to be the venues for disturbance and trouble, given their scope for jostling and proximity of rival large groups.

We strongly urge the retention of surviving and part-surviving multi-roomed layouts. They provide a more civilised drinking environment on top of their historic and social importance. Any proposals to remove walls should be resisted. Even widening of doorways can have a serious negative impact, especially as the door inevitably goes at the same time.

The tendency to upgrade all areas of a pub to the same standard throughout should also be avoided; maintaining differences in quality or design of decorations and furnishing between different areas of the pub does much to bring about individuality and appeal

White Hart, Midsomer Norton, Somerset

Internal Alterations and Extensions

Certain very rare or unaltered pubs should only be considered for sympathetic repair. However, in most cases refurbishment plans for a pub will go beyond conservation and repair of the existing fabric. The usual justification will be a need to upgrade facilities in line with modern hygiene or safety regulations or to meet increased public expectations on facilities or comfort. We would argue that such upgrading can generally be achieved without having to sacrifice what is historically important.

The underlying principles of successful refurbishment, as with interventions with any historic structure, can be summarised as 'working with the building'. Understanding the building and how it has developed, through research and architectural analysis, is therefore essential before plans for changes are drawn up.

Flexibility is the key when seeking to upgrade facilities. Different elements on the 'shopping list' should be fitted in to the existing building and layout, rather than imposed on it. Currently disused or under-used rooms or spaces can be examined, for instance, as a first port of call to see if they could accommodate the desired expansion or new facilities. Where changes to historic fabric are deemed unavoidable they should be kept to a minimum and, if possible, made reversible so that reinstatement is not ruled out.

Flexibility should be sought when dealing with the requirements of building and fire regulations or licensing authority concerns about supervision and public order. These may lead to demands for major alterations but in many cases a more sensitive solution can be negotiated; other officials may be persuaded to exercise a degree of discretion on interpreting regulations, particularly if a building is listed.

Where fitting desired facilities into the existing building just can't be done, an extension might be the answer. Design and scale must be carefully considered; it should complement, and not overwhelm, the parent building. A small, well-designed extension could accommodate, for instance, upgraded toilets which, if installed in the main body of the pub, could have a serious impact.

Where larger extensions are necessary in order to preserve the viability of the pub then the previously-mentioned approach for the Drewe Arms should be favoured where possible. Retaining historic elements whilst adding new facilities can be achieved if flair and imagination are brought to bear.

New fixtures and fittings, if needed, can either take their inspiration from those which survive (care being taken to match details of design as well as quality and durability of materials) or else may be of appropriate modern design. To be avoided at all costs are mass-produced 'Victorian' fittings and their ilk.

The following links take you to detailed information about three of the pubs which we consider to be superlative examples of sensitive refurbishment.

Drewe Arms, Drewesteignton, Devon

Princess Louise, Holborn, London

Three Pigeons, Halifax

External Alterations

Signage

Consent will normally be needed for a change of signage if the pub is listed (unless the sign is like-for-like).

There have been regrettable developments in signage recently with some breweries and pub companies favouring bland 'corporate' signs completely lacking in individuality.

Signage proposals are often linked to changes in a pub's trading style eg from traditional boozer to gastro pub. New signage to match the new image will usually form part of a larger planning application which makes it difficult to reject just that element. Stand-alone signage schemes will of course need advertising consent so can be challenged if they conflict with the style, ambience or architecture of the building. Where the desire is to 'make a change to attract more customers' then alternatives which could meet both that need and those of the building should be offered. Pub owners shouldn't be entitled to stick any old signage onto a pub without considering the features of the building - and a compromise can generally be found.

A strong case exists for promoting traditional wooden signboards over the 'plastic' affairs now often favoured. Advances in timber treatment and paint finishes mean that such signs can last a long time and they always look better.

Signwriting directly onto the building, if done well, can be very effective; it's a deeply traditional method too.

When submissions are made for signage (and lighting) it could be a condition that night-time visuals (or computer-generated photos) are available so that the effects at that time of day can be evaluated. Lighting can be subtle and effective - it doesn't have to be brash and intense.

Smoking Shelters

Several issues have arisen since these structures followed in the wake of the smoking ban. Applications for planning permission to erect them will of course be treated as for any extension and the same sensitivity to the main building must be demonstrated. Shelters look better if built from natural materials which blend with the pub itself. Positioning is also key, with the rear or side obviously being best but access to the bars, window positions and proximity to neighbours will also be factors. Ideally the shelter shouldn't be physically connected to the main building whilst not forcing smokers onto a route march.

Conclusions

Our main objective here is to encourage planners to pay particular attention to applications which affect historic pubs, especially those which are on CAMRA's National and Regional Inventories of Historic Pub Interiors. We very much hope therefore that they will take note of any of 'their' pubs which are on an Inventory and scrutinise proposals and applications concerning them very closely, taking account of this guidance and the aspects of architecture and design to which it draws attention.

We will always be delighted to work with planning authorities which find themselves dealing with applications for Inventory or listed pubs. We have accumulated a great deal of knowledge and experience in this area over the years and will only be too happy to offer what advice and suggestions we can.

Our pub heritage is a precious but threatened one and we very much hope that we can work together to prevent it dwindling still further.

Further Reading

'Licensed to Sell: The History and Heritage of the Public House' by Geoff Brandwood, Andrew Davison and Michael Slaughter (English Heritage 2004) is the definitive work on the development of pubs as buildings.

For a list of other books dealing with public houses from the standpoint of the architect, including advice on conservation, repair and sympathetic refurbishment see the Further Reading page.

CAMRA's Pub Heritage Group

Although many people associate CAMRA only with real ale, it also exists to promote and protect pubs. An important aspect of that work concerns our historic pubs and is led by CAMRA's Pub Heritage Group. The Group is responsible for both the National and the emerging Regional Inventories of pub interiors of historic and architectural importance. It also aims to promote interest in, and awareness of, historic pub interiors both within and outside CAMRA, along with pursuing the statutory listing of pubs with important interiors. Where such pubs are under threat, the Group will lead on or support campaigns to protect them.

Our website at www.heritagepubs.co.uk/home/home.asp includes a wealth of information about historic pubs, including the Inventories. It is linked to the main CAMRA website at www.camra.org.uk. You can contact the Group by:

Email: info@pubheritage.camra.org.uk

Telephone: 01727 867201

Letter: Pub Heritage Group, CAMRA, 230 Hatfield Road, St Albans, AL1 4LW